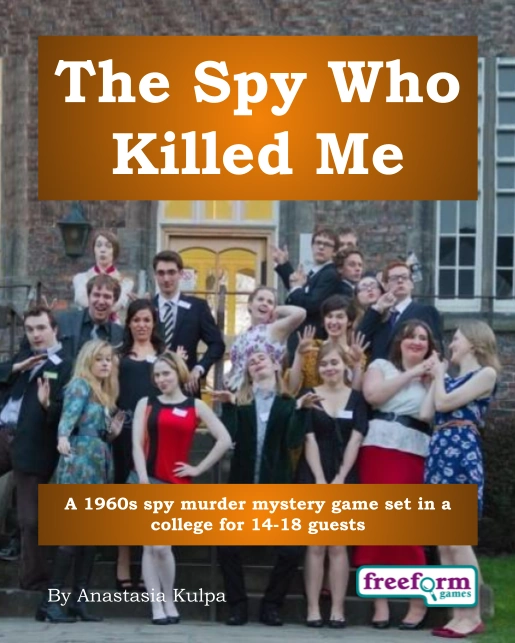

We’ve got something a bit different this time – a story from customer Mark Lemay about adding Skype and simple cryptography to The Spy Who Killed Me.

Here’s Mark:

When I ran The Spy Who Killed Me I created two additional characters who were only contactable by Skype. The players playing the characters were remote from the party, and I had two hidden laptops at the party.

The two characters were spymasters – the Soviet Heracles, and the British ‘S’. They joined the party 30 minutes after it started (which allowed the other players to start playing properly). Neither knew about the murder (until they were told about it by their agents).

I wrote full character sheets for the two spies, with background, goals and information about other people. The main difference between these characters and the other characters is that they would have to do everything remotely, through their agents.

Heracles’ contacts were given a telegram that said: “Comrade, We have established a secure line of communication. In the back of the kitchen there are stairs to the basement. At the bottom of the stairs go right. At the back of the of the basement I will be waiting. Don’t arouse suspicion. Be sure you are not followed. Heracles”

(Those players who needed to talk to ‘S’ were given a similar note.)

I also sent Heracles the telegram on page 17 of the cards file when the party started. The two agents texted me messages that they needed to send to their ‘agents’. The only way the agents to contact Heracles or ‘S’ was by Skype.

I set the Skype ringtones to the appropriate national anthem, and Heracles set his Skype up so that only a silhouette could be seen. Neither ‘S’ nor Heracles knew that there was another spy Skyping into the party, and none of the players (with the regular characters) suspected that their out-of-town friends would be making an appearance.

At about 9pm I gave Heracles’ contact details to ‘S’ so that she could try and trick some information out of him.

It was fun for the people involved, and went surprisingly unnoticed by the people who weren’t. The biggest issue I had was not making the strict deadlines of the party clear to the remote players. Also, if I did it again, I’d give ‘S’ a few clues as to how to trick Heracles (such as pretending to be an Indian spy).

Feedback from Heracles

My friend who played Heracles was nice enough to write up his thoughts on the experience:

It was always clear that my participation would be more limited than that of guests physically attending the party, but I still enjoyed my role. Like a normal character, I had secret knowledge, relationships with characters, and abilities. Despite my separation from the party, I felt that Mark gave me enough choices that I could still employ strategy and influence the course of events. I had a means of contacting other guests at the party, and an incentive to strategically hide certain information from some of my associates, which was fun to roleplay.

There were a few things that could be improved. I was slightly discouraged from speaking with guests too frequently, because Mark was worried that I would give away information too quickly and take them away from the rest of the guests. It turned out that I probably could have spoken to more guests, and more frequently. Because I was isolated I wasn’t entirely in the loop about the timeline, and when the party was ending.

Cryptography challenge

Instead of using the mechanics suggested in the instructions, I modified the item cards to have an actual encoded message – the message encoded with the reverse alphabet. I added an additional book to the library that had an explicit key.

This was the perfect level of difficulty and while one person solved it quickly, nobody took longer than ten minutes. Instead of disengaging from the party to solve the problem, the players could work together in small groups. It was also one less thing I had to referee.

The encoded journal

I tried a similar puzzled with the journal, but I didn’t want it to be too easy. I used a different substitution cypher on each page (but following a simple pattern) and left out spaces. I modified the key so it contained the information to decode the text.

A group of ‘student’ worked together to try and decode the journal. They became invested in solving the puzzle. Unfortunately, it was a little too hard (especially after all the drinks) and I had to give them the solution after 15-20 minutes. I think It would have worked out if I had left the spaces in the journal.

(A note from Steve and Mo: We don’t usually include codes like these to our games because it can be very difficult to judge player expertise. We also know how frustrating it can be to play an expert in codes but not be very good at it yourself. So we make sure we have other rules for dealing with codes. However, we’re always delighted when our customers change their games for their groups and incorporate these kinds of details.)

Staging the scene of the murder

I designated one small room as Beth’s room (the victim). This was mostly decoration, but the guests got pretty into it. First I thoroughly cleaned the room so there was nothing distracting – just a bed and a desk. On the floor, I made a roughly human shape out of (clean) laundry and covered it with a blanket. I put the description of the body under the blanket in case anyone looked. I decorated the room according to the description in the instructions. On the desk I put an assortment of math textbooks, and small photos of the boyfriend and best friend character.

At the beginning, after the introduction I announced that, “Beth’s room is up the stairs in the second room on the left… the police have asked the scene not be disturbed. So don’t go up there and try to investigate.”

It was good because even though only a few people would have thought to ask about the details of the room, everyone went up to see the room. Except the murderer, who purposely stayed away from it the entire night.

The Russian memo

I used Google translate to make a very Russian looking memo with the names and addresses in English and the names in bold.

I hid the telegram in a book and added its location into the encoded journal.

0 Comments